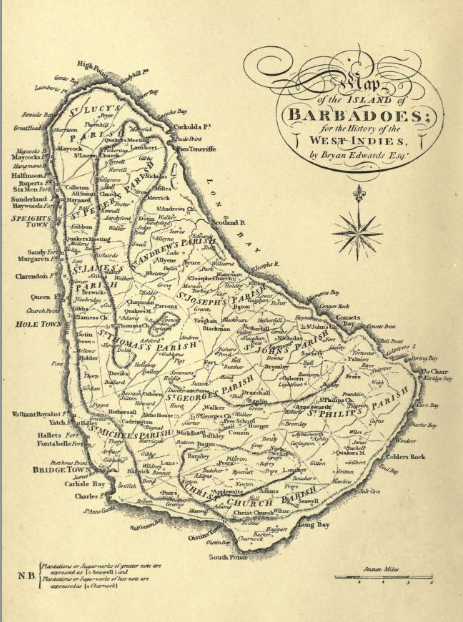

ALLEYNE FAMILY OF BARBADOES

This old house was acclaimed as the grandest local estate in the 17th and 18th centuries in Quincy, MA.. "The Quincy Homestead" was chosen for the National Register of Historic Places in 2005, because it represents the evolution of over 300 years of American architecture by combining Colonial, Georgian and Victorian design.

The Quincys were one of the leading families of Massachusetts. Their decendents include President John Quincy Adams and Dr. Oliver Wendell Holmes. It was the childhood home of the First Lady of Massachusetts, Dorothy Quincy Hancock, wife of John Hancock, first signer of the Declaration of Independence, and first governor of the state of Massachusetts.

The Massachusetts Colonial Dames negotiated a sale-leaseback agreement with the state in 1904 to save the mansion. The state is mostly responsible for the exterior and The Dames look after the interior. Since 2005, this old house has undergone much renovation to restore this stately historic building to its former grandeur.

The Quincys were one of the leading families of Massachusetts. Their decendents include President John Quincy Adams and Dr. Oliver Wendell Holmes. It was the childhood home of the First Lady of Massachusetts, Dorothy Quincy Hancock, wife of John Hancock, first signer of the Declaration of Independence, and first governor of the state of Massachusetts.

The Massachusetts Colonial Dames negotiated a sale-leaseback agreement with the state in 1904 to save the mansion. The state is mostly responsible for the exterior and The Dames look after the interior. Since 2005, this old house has undergone much renovation to restore this stately historic building to its former grandeur.

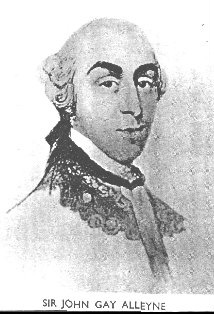

SIR JOHN GAY ALLEYNE

Falling sugar prices in Barbados forced the Nicholas family to sell the St. Nicholas Plantation in the mid-1720’s to Joseph Dottin. The Dottin family was prominent in Barbadian society; the appointment of Deputy Governor of Barbados had traditionally passed from Dottin father to son for many generations. Joseph Dottin owned several properties on the island and presented each of his daughters with a plantation as a wedding gift. He gifted Nicholas to his daughter, Christian, upon her marriage to Sir John Gay Alleyne in October 1746.

Sir John, himself a prominent member of the Barbados community, served as Speaker of the House of Assembly from 1767-1797 while also managing Mount Gilboa Plantation and Distillery for his close friend, John Sober. Sir John Gay Alleyne did such an excellent job managing that plantation, it was posthumously renamed Mount Gay in his honour and carries the name to this day.

Under Sir John's ownership a number of changes were made to St. Nicholas Plantation, including physical upgrades to the Great House. By this time the Jacobean style was considered dated; Sir John added the more modern triple arcaded portico, sash windows and intricate Chippendale staircase.

In honour of the Treaty of Paris, Sir John replaced the original Cherry Trees lining Cherry Tree Hill, the entrance to the Plantation, with Mahogany trees, the first of their kind on the island, which still stand today.

Perhaps the most significant contribution Sir John made to the plantation was introducing rum distillation as a mean of economic sustainability. Like most Barbadian plantations, Nicholas’ primary source of income was sugar and its related by-products. The plantation’s mill produced sugar and molasses in its early years, with production changing to syrup later on. These products, as well as the distilled rum, were exported to Europe and America. At the height of production, Nicholas was considered to be one of the most successful plantations in Barbados, and likely, the Caribbean.

After Christian’s death in 1782, Sir John Gay Alleyne married his cousin, Jane Abel Alleyne, daughter of Abel Alleyne and Mary Woodbridge. They had several children. Sir John continued to live at St. Nicholas until his death in 1801 (Jane died in 1800). Christian’s will had stipulated that St. Nicholas Plantation pass to her own children upon Sir John’s death; with no surviving heirs (their only son died at age 12 while at school at Eton), ownership reverted to the Dottin Family. Political difficulties in Europe and the start of the Napoleonic War made it near impossible to track down the Dottin descendants, who resided in several different countries. During the search the property incurred considerable debt and the property was taken by the Chancery Court in Bridgetown in 1810.

Sir John, himself a prominent member of the Barbados community, served as Speaker of the House of Assembly from 1767-1797 while also managing Mount Gilboa Plantation and Distillery for his close friend, John Sober. Sir John Gay Alleyne did such an excellent job managing that plantation, it was posthumously renamed Mount Gay in his honour and carries the name to this day.

Under Sir John's ownership a number of changes were made to St. Nicholas Plantation, including physical upgrades to the Great House. By this time the Jacobean style was considered dated; Sir John added the more modern triple arcaded portico, sash windows and intricate Chippendale staircase.

In honour of the Treaty of Paris, Sir John replaced the original Cherry Trees lining Cherry Tree Hill, the entrance to the Plantation, with Mahogany trees, the first of their kind on the island, which still stand today.

Perhaps the most significant contribution Sir John made to the plantation was introducing rum distillation as a mean of economic sustainability. Like most Barbadian plantations, Nicholas’ primary source of income was sugar and its related by-products. The plantation’s mill produced sugar and molasses in its early years, with production changing to syrup later on. These products, as well as the distilled rum, were exported to Europe and America. At the height of production, Nicholas was considered to be one of the most successful plantations in Barbados, and likely, the Caribbean.

After Christian’s death in 1782, Sir John Gay Alleyne married his cousin, Jane Abel Alleyne, daughter of Abel Alleyne and Mary Woodbridge. They had several children. Sir John continued to live at St. Nicholas until his death in 1801 (Jane died in 1800). Christian’s will had stipulated that St. Nicholas Plantation pass to her own children upon Sir John’s death; with no surviving heirs (their only son died at age 12 while at school at Eton), ownership reverted to the Dottin Family. Political difficulties in Europe and the start of the Napoleonic War made it near impossible to track down the Dottin descendants, who resided in several different countries. During the search the property incurred considerable debt and the property was taken by the Chancery Court in Bridgetown in 1810.