John Peter Van Ness Family

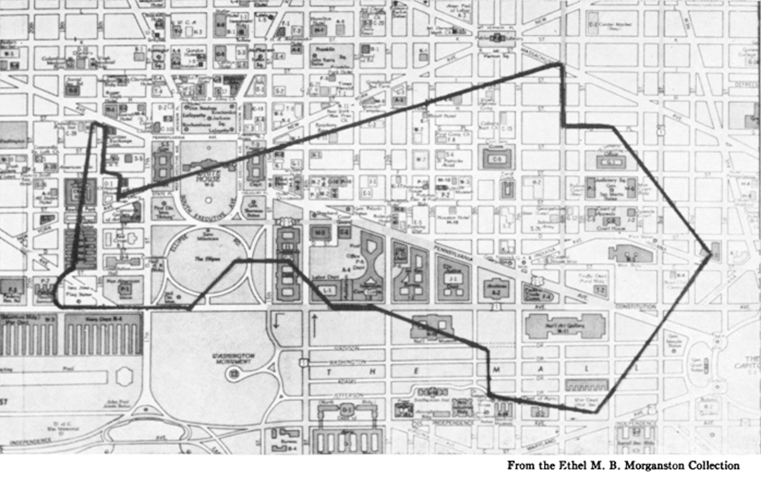

David Burnes Farm

David Burnes Cabin

Tonight as darkness approaches, six headless horses gallop around the site of the Van Ness Mansion (now site of the Organization of American States 17th St. between C St. and Constitution Ave., NW Washington D.C.) on the anniversary of the death of Gen John Van Ness*. (March 7, 1847) The following is the family story taken from the 1874, Ten Years in Washington; Life and Scenes as a Woman sees them, by Mary Clemmer Ames. Edited by Jan and Charles Handfield Wyatt IV

* General John P. Van Ness is the 3rd Great Grand Uncle of Charles Wyatt IV related through John’s brother William P.Van Ness, Charles’s 3rd Great Grandfather.

You remember him, he was Washington's “obstinate Mr. Burnes.” Well, he owned nearly the entire site of the future Federal city, an estate which had descended to him, through several generations of Scottish ancestors. It was perfectly human and right that he should make the most and best of his precious paternal acres. Long before quarrelling Congresses had even thought of the District of Columbia as a site to contend over as the future Capitol, the cottage of David Burns had gathered on its lowly roof the moss of time.

After the lapse of nearly a century it stands to-day as it stood then, only the moss on its roof is deeper, and the trees which arch above it, cast a longer and deeper shadow. It was a mansion in that day of small beginnings, Yet it is but a low, sharp-roofed cottage, one story high, with a garret; its doors facing north and south, one opening upon the river, with no steps, but one broad flag-stone, now settled deep within its grassy borders. Besides the garret, there cannot be more than four rooms in the house; a dining-room, sitting-room, and two sleeping-rooms; the kitchen, after the Maryland and Virginia fashion of the present day, was probably a detached building. The farm-house no doubt equalled its average neighbors, scattered miles apart across the wide domain of open country.

* General John P. Van Ness is the 3rd Great Grand Uncle of Charles Wyatt IV related through John’s brother William P.Van Ness, Charles’s 3rd Great Grandfather.

You remember him, he was Washington's “obstinate Mr. Burnes.” Well, he owned nearly the entire site of the future Federal city, an estate which had descended to him, through several generations of Scottish ancestors. It was perfectly human and right that he should make the most and best of his precious paternal acres. Long before quarrelling Congresses had even thought of the District of Columbia as a site to contend over as the future Capitol, the cottage of David Burns had gathered on its lowly roof the moss of time.

After the lapse of nearly a century it stands to-day as it stood then, only the moss on its roof is deeper, and the trees which arch above it, cast a longer and deeper shadow. It was a mansion in that day of small beginnings, Yet it is but a low, sharp-roofed cottage, one story high, with a garret; its doors facing north and south, one opening upon the river, with no steps, but one broad flag-stone, now settled deep within its grassy borders. Besides the garret, there cannot be more than four rooms in the house; a dining-room, sitting-room, and two sleeping-rooms; the kitchen, after the Maryland and Virginia fashion of the present day, was probably a detached building. The farm-house no doubt equalled its average neighbors, scattered miles apart across the wide domain of open country.

Marcia Burnes - Heiress to the City of Washington

George Washington by Gilbert Stuart

Before Washington came to negotiate for the future site of the Federal city, the society of Davy Burns was probably composed of plain farmer folk like himself. It was at a later time, when the farmer was transformed into a millionaire, and his only daughter had grown into the fairest belle and richest heiress in all the country round, that the long, low rooms of the one-story farmhouse were filled with the most illustrious men of their generation.

At the time of the sale of his estate to President Washington, David Burns' only daughter was not more than twelve or thirteen years of age.

With a prescience of her future lot, he proceeded to give her every advantage of education and society at that period accessible to a gentlewoman of fortune.

The Rector of St. John's Church, who preached her funeral sermon in 1832, said: “She was placed by her parents in the family of Luther Martin, Esq., of Baltimore, who was then at the height of his fame as the most distinguished jurist and advocate in the State of Maryland, and with his daughters and family she had the best opportunity of education and society.”

At eighteen, Marcia Burns returned to the home of her parents--the lowly farm-house on the banks of the Potomac. Then, and at a later day, when the flush and enchantment of youth had fled, the vision of Marcia Burns is altogether lovely. Beside the attractions of fortune, she seemed to possess in an eminent degree the highest qualities of the feminine nature. It was of Marcia Burns that Horatio Greenough (Sculptor of George Washington) wrote:

“'Mid rank and wealth and worldly pride,

From every snare she turned aside.

She sought the low, the humble shed,

Where gaunt disease and famine tread;

And from that time, in youthful pride,

She stood Van Ness's blooming bride,

No day her blameless head o'erpast,

But saw her dearer than the last.”

The return of the only child and heiress of David Burns, in the first beauty of young womanhood, soon filled the paternal cottage with illustrious society, and with many suitors for her hand and heart. The Keys, the Lloyds, the Peters, the Lows, the Tayloes, the Calverts, the Carrols, all visited here. Washington, Jefferson, Hamilton, Burr, with many other famous then, not forgotten now, were guests at the Burns cottage. Thomas Moore was entertained beneath its roof, and slept in one of the little rooms “off” the large one on the ground floor.

The favored suitor was John P. Van Ness, the son of Judge Peter Van Ness of New York, celebrated as an anti-Federalist, a Revolutionary officer, and a supporter of Aaron Burr against the Clinton and Livingston feud.

When John Van Ness wooed and won Marcia Burns, he was thirty years of age, a Member of Congress from New York, “well-fed, well-bred, well-read,” elegant, popular and handsome enough to win his way to any maiden's heart, unassisted by the accessories of fortune, which, in addition, were bountifully his.

At the time of the sale of his estate to President Washington, David Burns' only daughter was not more than twelve or thirteen years of age.

With a prescience of her future lot, he proceeded to give her every advantage of education and society at that period accessible to a gentlewoman of fortune.

The Rector of St. John's Church, who preached her funeral sermon in 1832, said: “She was placed by her parents in the family of Luther Martin, Esq., of Baltimore, who was then at the height of his fame as the most distinguished jurist and advocate in the State of Maryland, and with his daughters and family she had the best opportunity of education and society.”

At eighteen, Marcia Burns returned to the home of her parents--the lowly farm-house on the banks of the Potomac. Then, and at a later day, when the flush and enchantment of youth had fled, the vision of Marcia Burns is altogether lovely. Beside the attractions of fortune, she seemed to possess in an eminent degree the highest qualities of the feminine nature. It was of Marcia Burns that Horatio Greenough (Sculptor of George Washington) wrote:

“'Mid rank and wealth and worldly pride,

From every snare she turned aside.

She sought the low, the humble shed,

Where gaunt disease and famine tread;

And from that time, in youthful pride,

She stood Van Ness's blooming bride,

No day her blameless head o'erpast,

But saw her dearer than the last.”

The return of the only child and heiress of David Burns, in the first beauty of young womanhood, soon filled the paternal cottage with illustrious society, and with many suitors for her hand and heart. The Keys, the Lloyds, the Peters, the Lows, the Tayloes, the Calverts, the Carrols, all visited here. Washington, Jefferson, Hamilton, Burr, with many other famous then, not forgotten now, were guests at the Burns cottage. Thomas Moore was entertained beneath its roof, and slept in one of the little rooms “off” the large one on the ground floor.

The favored suitor was John P. Van Ness, the son of Judge Peter Van Ness of New York, celebrated as an anti-Federalist, a Revolutionary officer, and a supporter of Aaron Burr against the Clinton and Livingston feud.

When John Van Ness wooed and won Marcia Burns, he was thirty years of age, a Member of Congress from New York, “well-fed, well-bred, well-read,” elegant, popular and handsome enough to win his way to any maiden's heart, unassisted by the accessories of fortune, which, in addition, were bountifully his.

In Gilbert Stuart's picture we see him with powdered wig and toupee, light-brown hair and side whiskers, perceptive forehead, aquiline nose, finely-curved lips and chin, a small mouth, with clear, hazel eyes, which could look their way straight to many hearts.

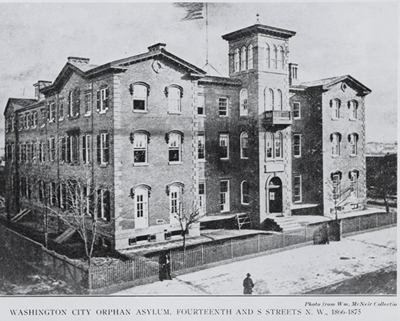

The portrait of the heiress of Robert David Burns may be seen to-day in Washington, not in any hall of wealth or fashion, but in the Orphan Asylum, which she founded and endowed, to whose children she was a mother. It looks down upon us, a Madonna face, with intellectual, spiritual brow, dewy eyes, and a tender mouth.

(Now at Edgewater, Barrytown, NY - Richard Jenrette)

Marcia Burns married John P. Van Ness at the age of twenty. Her only brother dying in early youth, she inherited the whole of her father's vast estate. For a few years after her marriage she lived at the old cottage.

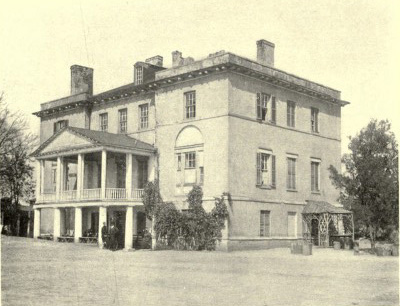

Her husband then built a two-story house on the corner of Twelfth and D streets. Later, he began the house, which, still standing in the centre of Mansion Square, is one of the most unique of all the historic houses of Washington. It was designed, as were so many famous Washington houses, by Latrobe, and cost between $50,000 and $60,000 more than half a century ago. Its marble mantel-pieces, wrought in Italy, with their sculptured Loves and Vestas, still remain, models of exquisite art. It is finished with costly woods, and about its door-knobs are set tiles inlaid with Mosaics. Its great portico, facing north, is modeled after that of the President's house. This stately brick mansion, amid the trees, standing a few rods back from the Burns' cottage, presents to it an absolute contrast (1874).

The portrait of the heiress of Robert David Burns may be seen to-day in Washington, not in any hall of wealth or fashion, but in the Orphan Asylum, which she founded and endowed, to whose children she was a mother. It looks down upon us, a Madonna face, with intellectual, spiritual brow, dewy eyes, and a tender mouth.

(Now at Edgewater, Barrytown, NY - Richard Jenrette)

Marcia Burns married John P. Van Ness at the age of twenty. Her only brother dying in early youth, she inherited the whole of her father's vast estate. For a few years after her marriage she lived at the old cottage.

Her husband then built a two-story house on the corner of Twelfth and D streets. Later, he began the house, which, still standing in the centre of Mansion Square, is one of the most unique of all the historic houses of Washington. It was designed, as were so many famous Washington houses, by Latrobe, and cost between $50,000 and $60,000 more than half a century ago. Its marble mantel-pieces, wrought in Italy, with their sculptured Loves and Vestas, still remain, models of exquisite art. It is finished with costly woods, and about its door-knobs are set tiles inlaid with Mosaics. Its great portico, facing north, is modeled after that of the President's house. This stately brick mansion, amid the trees, standing a few rods back from the Burns' cottage, presents to it an absolute contrast (1874).

The Van Ness Mansion

This costly home was ready for the family when the only daughter and child of General and Mrs. Van Ness returned, in 1820, from school in Philadelphia. Thither Marcia Burns brought her daughter. The bond between the two is said to have been more intimate and profound than that of simply mother and daughter. The daughter was the cherished companion of the mother, who cultivated an intelligent interest in public affairs, who loved poetry, and wrote it, and who, amid all the pomp of wealth and state, never forgot, or allowed her child to forget, that the fashion of this world passeth away.

Ann Elbertina Van Ness married Arthur Middleton of South Carolina, son of a signer of the Declaration of Independence. But, in November, 1822, in less than two years from her return from school, this only child, this youthful bride, this heiress of untold wealth, with her babe in her arms, was carried to the grave.

From that hour, her mother, Marcia Burns, who, in the world, had never been of it, renounced its vanities entirely. The cottage in which she was born, in which her parents lived and died, nestling under the patriarchal trees, just outside the windows of her stately home, had ever remained the object of her veneration and affection. In this humble dwelling, over whose venerable roof waved the branches of trees planted by her dear parents, she selected a secluded apartment, with appropriate arrangements for solemn meditation, to which she often retired, and spent hours in quiet solitude and holy communion.

Ann Elbertina Van Ness married Arthur Middleton of South Carolina, son of a signer of the Declaration of Independence. But, in November, 1822, in less than two years from her return from school, this only child, this youthful bride, this heiress of untold wealth, with her babe in her arms, was carried to the grave.

From that hour, her mother, Marcia Burns, who, in the world, had never been of it, renounced its vanities entirely. The cottage in which she was born, in which her parents lived and died, nestling under the patriarchal trees, just outside the windows of her stately home, had ever remained the object of her veneration and affection. In this humble dwelling, over whose venerable roof waved the branches of trees planted by her dear parents, she selected a secluded apartment, with appropriate arrangements for solemn meditation, to which she often retired, and spent hours in quiet solitude and holy communion.

The offering to God which she made beside the grave of her daughter, was the City Orphan Asylum of Washington. She became a mother to the children, saved, sheltered, and trained for heaven beneath its roof. She did not wait for these orphans to come to her door. Night and day she sought them out. In her portrait, still hanging in this asylum, she is sitting with three little girls, clinging to her for protection, one with its head in her lap.

Her last sickness was long and painful. A few days before her death, with a few Christian friends gathered about her bed, she celebrated the holy Sacrament; then, with perfect serenity, awaited the final call. Her last words to her husband, placing her hand upon his head, were: “Heaven bless and protect you. Never mind me.” She died September 9, 1832, aged fifty years.

She was the first American woman buried with public honors. At the time of her death, General Van Ness was Mayor of Washington. Meetings of condolence were held by citizens in different places. As the funeral procession began to move, a committee of citizens placed a second silver plate upon her coffin, inscribed:--

“The Citizens of Washington, in testimony of their veneration for departed worth, dedicate this plate to the memory of Marcia Van Ness, the excellent consort of J. P. Van Ness. If piety, charity, high principle and exalted worth could have averted the shafts of fate, she would still have remained among us, a bright example of every virtue. The hand of death has removed her to a purer and happier state of existence; and, while we lament her loss, let us endeavor to emulate her virtues.”

The procession passed between the little girls of the Orphan Asylum, who stood in lines, till the coffin was placed at the door of the vault, when they came forward, strewing the bier with branches of weeping-willows, and singing a farewell hymn.

The last earthly house which received the body of Marcia Burns was more magnificent than any she had ever inhabited. Years before, General Van Ness had reared a Mausoleum, which still remains, one of the purest examples of monumental art on this continent.

Her last sickness was long and painful. A few days before her death, with a few Christian friends gathered about her bed, she celebrated the holy Sacrament; then, with perfect serenity, awaited the final call. Her last words to her husband, placing her hand upon his head, were: “Heaven bless and protect you. Never mind me.” She died September 9, 1832, aged fifty years.

She was the first American woman buried with public honors. At the time of her death, General Van Ness was Mayor of Washington. Meetings of condolence were held by citizens in different places. As the funeral procession began to move, a committee of citizens placed a second silver plate upon her coffin, inscribed:--

“The Citizens of Washington, in testimony of their veneration for departed worth, dedicate this plate to the memory of Marcia Van Ness, the excellent consort of J. P. Van Ness. If piety, charity, high principle and exalted worth could have averted the shafts of fate, she would still have remained among us, a bright example of every virtue. The hand of death has removed her to a purer and happier state of existence; and, while we lament her loss, let us endeavor to emulate her virtues.”

The procession passed between the little girls of the Orphan Asylum, who stood in lines, till the coffin was placed at the door of the vault, when they came forward, strewing the bier with branches of weeping-willows, and singing a farewell hymn.

The last earthly house which received the body of Marcia Burns was more magnificent than any she had ever inhabited. Years before, General Van Ness had reared a Mausoleum, which still remains, one of the purest examples of monumental art on this continent.

The Van Ness Monument

It is a copy of the Temple of Vesta, and could not be built at the present time for a sum less than thirty-four or thirty-five thousand dollars (1874). In the vault, beneath its open dome, Marcia Burns was laid beside her child (and grandchild). This magnificent temple of the dead was recently removed to the Oak Hill Cemetery, Georgetown and rebuilt, precisely as it was in. The cells of its deep vault now hold nearly all of the dust left of the Burns and Van Ness alliance.

General Van Ness lived to the period of the Mexican war, passing away at the age of seventy-six, after having enjoyed every honor which the citizens of Washington could bestow upon him. He sued the Government of the United States for violating its contract with the original proprietors of Washington in selling to private purchasers lots near the Mall. Robert B. Taney was his lawyer, and yet he lost his suit. He gave an entertainment to Congress every year up to the time of his death, and wonderheads declare that his six horses, headless, still gallop around the Van Ness Mansion, in Mansion square, annually, on the anniversary of that event. (March 7, 1847)

Some twenty-five years ago (1849), this old mansion and estate was bought by its present proprietor, Thomas Green, Esq., a Virginia gentleman. The last time that it came prominently before the public, was during the assassination conspiracy, when an irresponsible newspaper sent the report flying that its great wine-vault was to have been used as a place of incarceration for Mr. Lincoln, before he was conveyed across the river. In those mad days no magnate waited for proof, and the result was that Mr. Green and his gentle wife, who,--as her husband remarked--“was as innocent as an angel,” were shut up in our small bastile, the old Capital prison. Here both were held for more than thirty days, when after having vindicated their honor beyond the possibility of reproach, the Government somewhat ashamed of itself, let them depart to the shelter of their patriarchal home.

On buying the estate, Mr. Green with that veneration for old, sacred associations which pre-eminently marks the Virginian,--instead of tearing down the old Burns' cottage as “nothing to him” or as a blot upon his fair estate, went immediately to work to preserve it. Without changing it in any way, he re-roofed it, made it rainproof, whitewashed it, and left it with its trees and memories.

What Mr. Green has preserved, let not the Board of Public Works destroy! In this case, gentlemen, let your “grade” go--and the cottage of “the obstinate Mr. Burns,” the first owner of this great Capital, and the oldest house in it--remain.

It was a June evening that we last passed the gate and the lodge of the old Van Ness estate, at the foot of Seventeenth street. The high brick-wall which shut in this historic garden, is mantled with ivy and honeysuckle. Old fruit trees, apple, pear, peach, apricot, plum, cherry, nectarine, and fig trees, all in their season, lift their crowns of fruitage to the sun within these old walls. Following a winding avenue, we pass through grounds above which gigantic aspen, maple, walnut, holly, and yew trees cast deep, cool shadows in the hottest summer days. As we approach the house we see that the drive before the northern portico is encircled with an immense growth of box. Before the low windows of the eastern drawing-room, stretch wide parterres of roses of every known variety. In June it is literally a garden of roses--and the early snow falls upon them, budding and blooming still in the delicious air. Oranges ripen on the sunshiny lawn which surrounds the house, and masses of honeysuckle which climb the balustrades of the southern portico pervade the air with sweetness, acres away.

This southern portico used as a conservatory in the winter, is a counterpart, on a smaller plan, of the south veranda of the President's house. It has the same outlook only nearer the river. To the right, the dome of the observatory swells into the blue air, and, before it, the Potomac runs up and kisses the grasses at its feet. Lovers' walk, shaded by murmuring pines, as such a walk should be, runs on through the grove down to a mimic lake, there, in mid-water, is a tiny island with shadowy trees and restful seats.

I stray down this walk with Alice,--golden-haired and poet-eyed. We wander across under the patriarchal trees and come out on the river-side of the old Burns' cottage. Its sunken door-stone, its antique door-latch, its minute window-panes, all are just the same as when Marcia Burns, beautiful and young, received within its walls her courtly worshippers; just the same as when Marcia Burns, smitten and childless, knelt alone by its desolate hearth, to commune with the God and Father of her spirit, and to dedicate herself to His service for ever.

Beside us, eight lofty Kentucky coffee-trees soar palmlike towards the sky. Through their clustering crowns the full moon peers down upon us; upon the cottage, so fraught with the memories of buried generations; upon the white walls of the mansion, so rich in recollections of the illustrious dead of a later past,--and she transfigures both cottage and hall in her hallowing radiance, as, with lingering steps, I say to gentle host and hostess, and to Alice,--golden-haired and poet-eyed,--“Farewell.”

General Van Ness lived to the period of the Mexican war, passing away at the age of seventy-six, after having enjoyed every honor which the citizens of Washington could bestow upon him. He sued the Government of the United States for violating its contract with the original proprietors of Washington in selling to private purchasers lots near the Mall. Robert B. Taney was his lawyer, and yet he lost his suit. He gave an entertainment to Congress every year up to the time of his death, and wonderheads declare that his six horses, headless, still gallop around the Van Ness Mansion, in Mansion square, annually, on the anniversary of that event. (March 7, 1847)

Some twenty-five years ago (1849), this old mansion and estate was bought by its present proprietor, Thomas Green, Esq., a Virginia gentleman. The last time that it came prominently before the public, was during the assassination conspiracy, when an irresponsible newspaper sent the report flying that its great wine-vault was to have been used as a place of incarceration for Mr. Lincoln, before he was conveyed across the river. In those mad days no magnate waited for proof, and the result was that Mr. Green and his gentle wife, who,--as her husband remarked--“was as innocent as an angel,” were shut up in our small bastile, the old Capital prison. Here both were held for more than thirty days, when after having vindicated their honor beyond the possibility of reproach, the Government somewhat ashamed of itself, let them depart to the shelter of their patriarchal home.

On buying the estate, Mr. Green with that veneration for old, sacred associations which pre-eminently marks the Virginian,--instead of tearing down the old Burns' cottage as “nothing to him” or as a blot upon his fair estate, went immediately to work to preserve it. Without changing it in any way, he re-roofed it, made it rainproof, whitewashed it, and left it with its trees and memories.

What Mr. Green has preserved, let not the Board of Public Works destroy! In this case, gentlemen, let your “grade” go--and the cottage of “the obstinate Mr. Burns,” the first owner of this great Capital, and the oldest house in it--remain.

It was a June evening that we last passed the gate and the lodge of the old Van Ness estate, at the foot of Seventeenth street. The high brick-wall which shut in this historic garden, is mantled with ivy and honeysuckle. Old fruit trees, apple, pear, peach, apricot, plum, cherry, nectarine, and fig trees, all in their season, lift their crowns of fruitage to the sun within these old walls. Following a winding avenue, we pass through grounds above which gigantic aspen, maple, walnut, holly, and yew trees cast deep, cool shadows in the hottest summer days. As we approach the house we see that the drive before the northern portico is encircled with an immense growth of box. Before the low windows of the eastern drawing-room, stretch wide parterres of roses of every known variety. In June it is literally a garden of roses--and the early snow falls upon them, budding and blooming still in the delicious air. Oranges ripen on the sunshiny lawn which surrounds the house, and masses of honeysuckle which climb the balustrades of the southern portico pervade the air with sweetness, acres away.

This southern portico used as a conservatory in the winter, is a counterpart, on a smaller plan, of the south veranda of the President's house. It has the same outlook only nearer the river. To the right, the dome of the observatory swells into the blue air, and, before it, the Potomac runs up and kisses the grasses at its feet. Lovers' walk, shaded by murmuring pines, as such a walk should be, runs on through the grove down to a mimic lake, there, in mid-water, is a tiny island with shadowy trees and restful seats.

I stray down this walk with Alice,--golden-haired and poet-eyed. We wander across under the patriarchal trees and come out on the river-side of the old Burns' cottage. Its sunken door-stone, its antique door-latch, its minute window-panes, all are just the same as when Marcia Burns, beautiful and young, received within its walls her courtly worshippers; just the same as when Marcia Burns, smitten and childless, knelt alone by its desolate hearth, to commune with the God and Father of her spirit, and to dedicate herself to His service for ever.

Beside us, eight lofty Kentucky coffee-trees soar palmlike towards the sky. Through their clustering crowns the full moon peers down upon us; upon the cottage, so fraught with the memories of buried generations; upon the white walls of the mansion, so rich in recollections of the illustrious dead of a later past,--and she transfigures both cottage and hall in her hallowing radiance, as, with lingering steps, I say to gentle host and hostess, and to Alice,--golden-haired and poet-eyed,--“Farewell.”

Your browser does not support viewing this document. Click here to download the document.